What happens when you visit a website?

We browse the web everyday, but what’s happening under the hood when we request a webpage? This post will attempt to summarize what I’ve learned after reading a bunch of articles!

Let’s say we want to visit https://stackoverflow.com in the browser, what happens after I send that request?

Step 1. DNS Lookup 🔎

The first thing the browser does is to try and find the IP address that corresponds to the domain you requested. It will first check the browser, DNS, and router cache for a matching record. If no match is found, the browser will query the recursive DNS resolver, which will begin a series of queries:

- The resolver queries the root nameserver, which returns the address of a top level domain (TLD) server -

.comin our case - The resolver queries the

.comTLD server, which returns the IP of the authoritative nameserver - The resolver queries the authoritative nameserver, which returns the IP for

stackoverflow.com

Once the correct IP is found and returned, it will be cached by the recursive DNS server for a period of time (roughly equal to the TTL defined in the DNS record) so future resolution of the same DNS query will be much faster.

Step 2. Establish a TCP connection with the server 🔌

The browser then opens a TCP connection with the server (which lives at the IP address returned from our DNS lookup) via a TCP handshake:

- The browser sends a

SYNmessage to the server to initiate a connection - The server responds with a

SYN-ACK - The browser sends an

ACKback to the server, - We now have a TCP connection opened with our server!

Step 3. Establish a TLS connection with the server 🔐

If you’re using HTTPS, the browser will now establish a TLS connection on top of the TCP connection via a TLS handshake. This is where the browser and server authenticate each other and obtain a session key that will be used to encrypt all communications between our browser and the server.

Step 4. Networking models IRL! ⚡️

Before we can send our data, we have to prep it with a bunch of additional information so that we can ensure nothing gets lost/corrupted and the data make it to the right place.

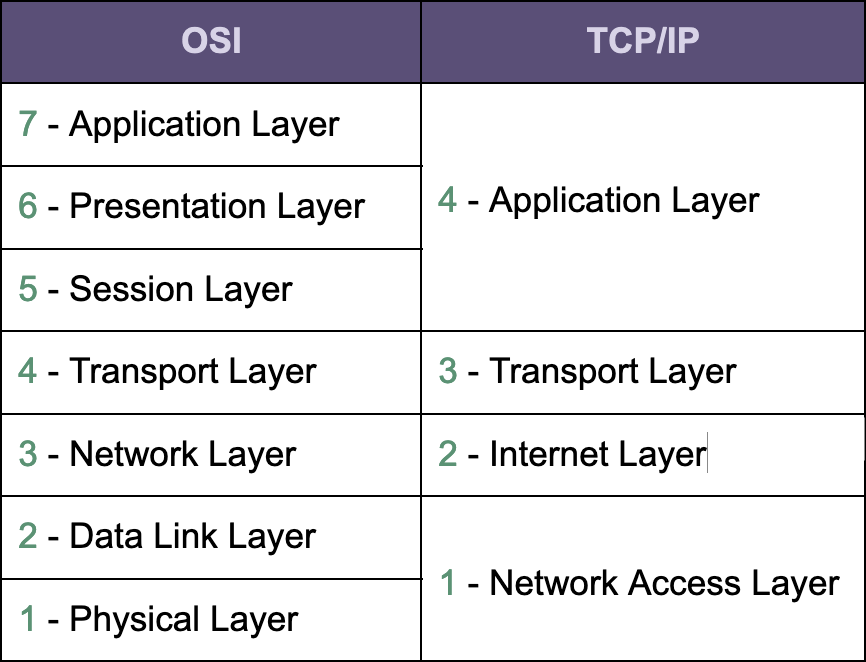

This is where the TCP/IP and OSI models come in. Note that although TCP/IP is what’s actually implemented IRL, I’ll follow the convention of using OSI terms to refer to the networking layers.

Starting at the application layer, we have the data we want to send, and it looks like this (this would be encrypted when using HTTPS):

GET / HTTP/2

Host: stackoverflow.com

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10.15; rv:94.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/94.0

...

As we move down the networking stack, this data is encapsulated with numerous headers, each containing pieces of the information about where the data is supposed to go:

- At the transport layer (layer 4), a TCP header is added to the data that specifies the port the data should be sent to at the destination. Our data at this point is called a segment.

- At the network layer (layer 3), an IP header is added to specify the source and destination IP addresses. At this point our packet is fully formed.

- At the data link layer (layer 2), the final header is added, and our packet becomes a frame. This contains information about the source and destination MAC addresses of the router that the switch in our network is connected to. A trailer is also added for error detection purposes.

Now our frame arrives at the router. Because routers deal with IPs, it will:

- Remove the frame headers to reveal the packet

- Look at the **header of the packet

- Consult its routing table to figure out where to send the packet (usually to another router)

- Add a new layer 2 header to the packet (containing the MAC address of the next location the frame should go to), turning it back into a frame and ready to go.

At this point, our request has finally left our network and travelling across the internet to the destination server! 🚀

Step 5. Server receives our request 📨

At the destination, the frame will now “traverse” up the network stack:

- At the data link layer, the destination device checks the MAC address in the frame’s header to make sure it matches the device’s own MAC address. There is also some error checking at this point to ensure the integrity of the data. If all checks pass, then the frame’s header and trailer are removed and sent to the next layer.

- At the network layer, check the IP address in the layer 3 header is correct, then removes that header.

- At the transport layer, check the port in the TCP header, removes that header, and sends our data to the application located at the specified port.

Step 6. Application responds to the request 🚀

The web server software on the destination server reads our request and returns either static content or forwards the request to the application server if dynamic content is requested.

The response assembled by the web server looks something like this:

HTTP/2 200 OK

cache-control: private

content-type: text/html; charset=utf-8

content-encoding: gzip

...

<!DOCTYPE html>

<HTML>

...

</HTML>

The response is sent back to the browser over the same TCP connection that was opened in step 2. The browser will then render the HTML/CSS/javascript files, and our request is complete!

It’s pretty wild to think that all of this happens a million times a day!